Python Basics - Variables and Data Types

Getting started with Python programming

If you are new to Python programming, I recommend you start with this module:

Before we get into the details of Python syntax, let’s consider the objectives of programming. In general, programming languages can be used for many things - software development, web development, analysis, modelling, automation, and so on. Other tools like MS Excel can also be used for these purposes, but the popularity of programming languages has increased because they are better able to handle large volumes of data.

The first step of building a program with Python (or any language for that matter) is to design the workflow and logic, at least at a conceptual level. This will help inform our approach and program structure. For example, suppose we want to conduct an analysis on a data set. Our workflow might include:

Defining the problem

Identifying the data points we need to solve the problem

Writing a SQL query to extract data

Saving the data to a csv file

Importing the csv file into a Jupyter notebook

Calculating summary statistics for each column

Filter data based on different segments and re-calculate summary statistics

From a Python programming perspective, we would start at step 3. This means that we need to build a short program which can read a csv file into a notebook. Then we would need to store the data into a variable (for example, a table), and then use some functions to calculate summary statistics.

For this tutorial, we will use a Python IDE. I recommend Jupyter Notebook or Google Colab.

Variables in Python

Variables in programming are a method of storing something, and then recalling it as much as we need to. You’ve likely seen variables in the past, for example - math class. Suppose you had a math problem:

x = 5

y = 6

x + y = z

5 + 6 = 11

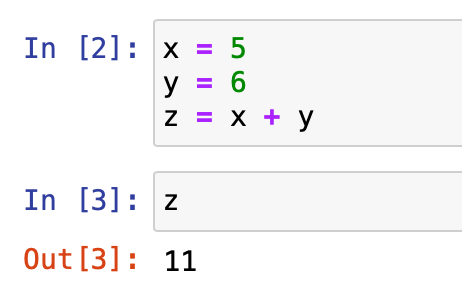

In this example, we’ve defined x and y as 5 and 6 respectively, and z as the sum of x and y. x, y and z are all variables. In Python, the process is very similar. Let’s practice defining and calling variables in Jupyter:

x = 5

y = 6

z = x + y

zYour output should look something like this:

Variables can hold individual data points, like 5 or 6, or objects. If you recall from the prior module, object-oriented programming allows us to work with classes which serve as blueprints of an object. Then we can create as many instances of an object as we want. A variable can hold a sentence, a list, a table, and more.

Data Types

There are several data types in Python, but the ones you will work with as a beginner are:

integer = 5

float = 5.3

boolean = True, False

string = "Text data is considered a string"There are also several types which hold multiple data points. These include:

lists = [1,2,3,4]

tuples = (1,2,3,4)

sets = {1,3,4}

dictionaries = {"key":"value", "key2":"value2:} Let’s discuss each individually, but first - why do we care about data types? Data types matter because different types will have access to different functions or capabilities. Also, functions in Python usually take various parameters (or instructions), and these parameters may have constraints about the format (or data type) in which they are entered. Let’s review the types of data we typically deal with in Python:

An integer is a whole number, like 5 or 10

A float is a number with a decimal point, like 5.4 or 7.34

A boolean value is a binary output, usually True or False, without quotations. Boolean values are also equivalent to 1 and 0 respectively (True = 1, False = 0).

A string is text data, for example a sentence or a word.

The types which consist of multiple data points are:

Lists, which are created using square brackets [ ]

Tuples, which are created using round brackets ( )

Sets, which use curly brackets { }

Dictionaries, which also use curly brackets, however they consist of key / value pairs separated by a colon :

As you can see, all data types have different characteristics. The first step in learning how to work with Python will be to learn how to manipulate and work with data types.

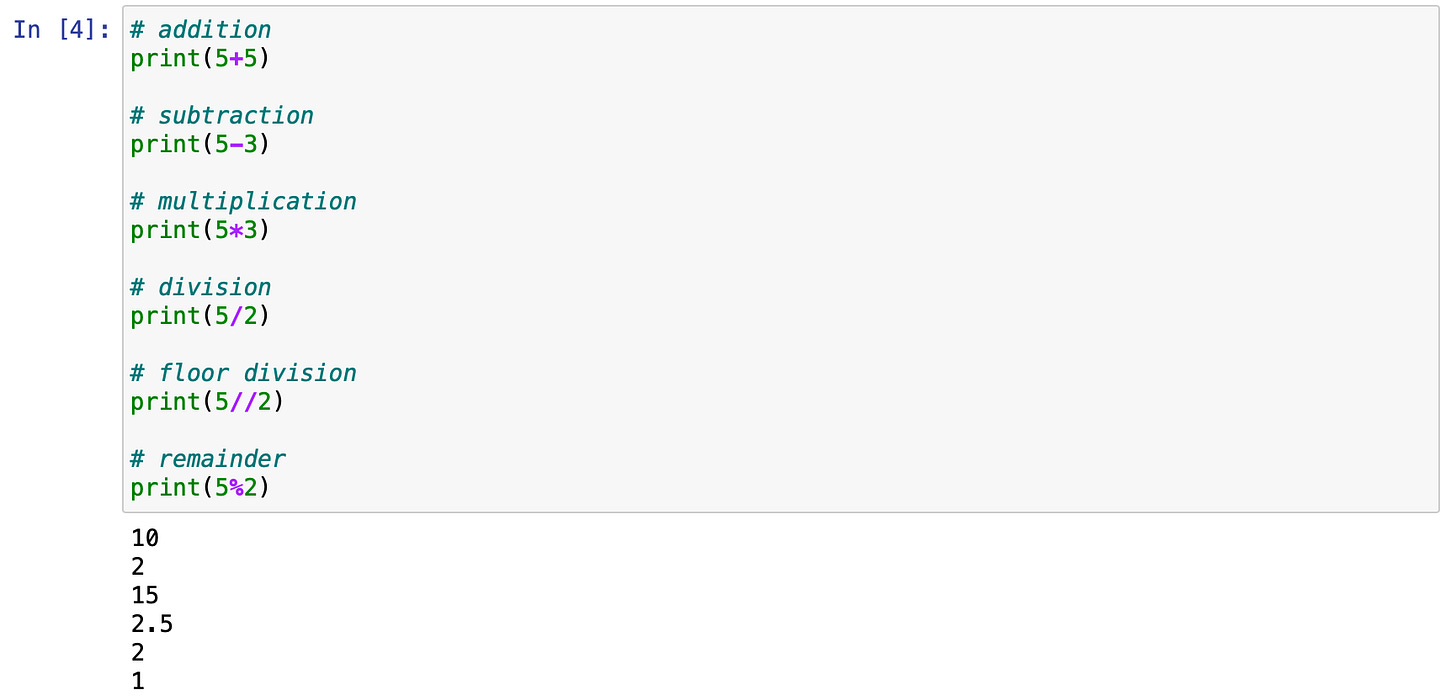

Integers and floats are essentially just numbers. We can perform basic calculations with them. In the following code blocks, you will notice some statements with a hashtag (#) symbol in front of them. These are comments. Comments are non-executable lines, and we generally use them to explain what the code is doing. It is a good practice to get in the habit of commenting your code, so if you come back to it, you can remember what you did and why.

The following are examples of mathematical operations, with input and output examples. You should :

# addition

print(5+5)

# subtraction

print(5-3)

# multiplication

print(5*3)

# division

print(5/2)

# floor division

print(5//2)

# remainder

print(5%2)Try these yourself by copying and pasting the code in a Jupyter notebook. Your output should look something like this:

You will notice that all of the outputs are integers, except for the output of 2.5 which corresponds to the line print(5/2). In general, division always returns a float value.

Floor division returns the whole number from the division, without the remainder. In this case, 5. The remainder (1) can be returned by using the modulo (%) instead of the slash (/).

You’ll also notice I’ve used the print() function. This is a function we use to display an output.

Let’s try creating some other objects:

list1 = [1,2,3,4] # create a list

print(list1) # output the list

set1 = {1,2,3,4}

print(set1)

tuple1 = (1,3,4,5)

print(tuple1)In addition to the terms “integer”, “float”, “string”, “list”, “tuple” and “set”, we can also use these as functions. For example, we could convert a list to a tuple, like this:

tuple2 = tuple(list1)

print(tuple2)We could convert an integer to a float:

print(float(5))You will notice here, that I did not define a new variable. In fact, I simply placed the operation inside a print() statement. This is an example of combining functions together.

We can also convert floats to integers, and either to a string:

print(int(5.3))

print(str(5))

print(str(5.4))You can check the data type of any variable using the type() function:

print(type(str(5.4)))General Structure of Python Functions

Python has a number of built-in functions, such as print() and type(). Generally, a built-in function starts with the function name, in this case “print” or “type”, followed by a set of brackets. Inside the brackets, we typically specify the parameters. Parameters can include the object we apply the function to, and any constraints.

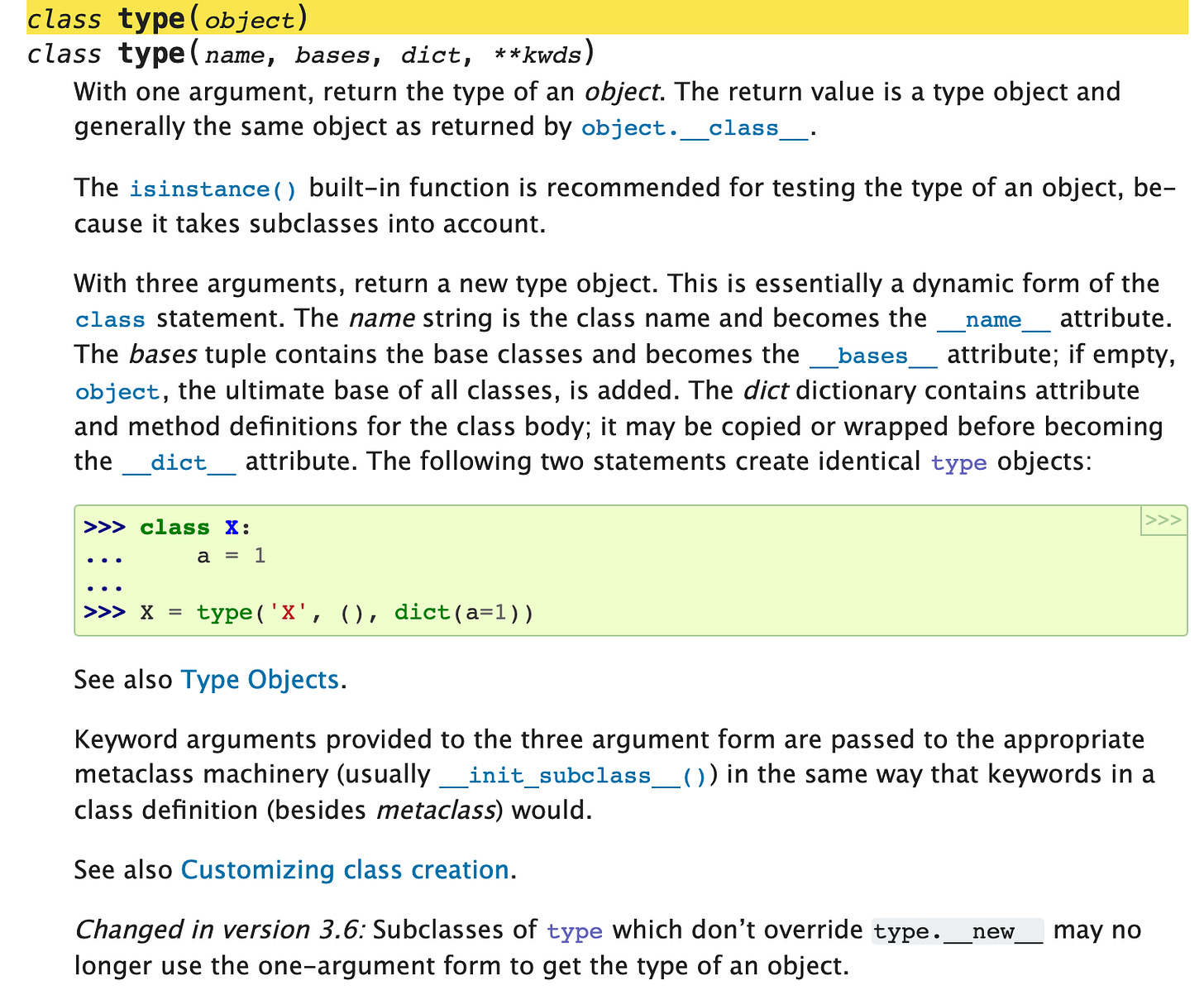

We can use documentation to learn about the parameters of different functions. Python’s documentation can be found here: https://docs.python.org/3/

Typically, you can Google specific functions for quick access to the documentation. Let’s take a look at the documentation for the type() function:

This looks quite complex! But we want to focus on the top part first:

We can see here that this function is of the class “type”. Inside the brackets, we are supposed to place an “object”. An object will refer to anything - a variable, a list, a tuple, a dictionary, and so on. The term “object” in the documentation is a parameter.

Certain functions expect certain types of objects, for example an iterable, which refers to a list, tuple, dictionary. The documentation will list specific requirements of any function. We will cover this again in further modules.